East Asia includes the People's Republic of China, North and South Korea, and Japan as well as Mongolia and Vietnam. The region is enormous and densely populated, with a complex history.

The earliest humans in what we know today as China date to 250,000 years ago and are evidenced by fossils in a cave found near present-day Beijing. In ancient times, the land alongside the Yellow River was not associated with a particular political entity, but was called the Middle Kingdom (Zhongguo in Mandarin Chinese). Pottery shards have been found dating to 10,000 BCE, and these shards begin to show evidence of the use of lacquer by 5000 BCE. Also around that time, during the late Neolithic period,

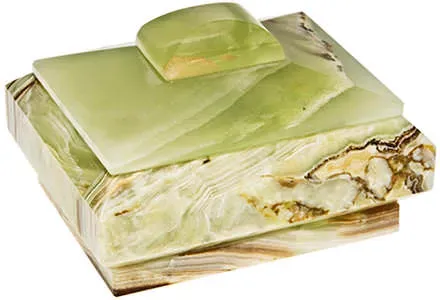

The earliest humans in what we know today as China date to 250,000 years ago and are evidenced by fossils in a cave found near present-day Beijing. In ancient times, the land alongside the Yellow River was not associated with a particular political entity, but was called the Middle Kingdom (Zhongguo in Mandarin Chinese). Pottery shards have been found dating to 10,000 BCE, and these shards begin to show evidence of the use of lacquer by 5000 BCE. Also around that time, during the late Neolithic period, ![]() jade carvings begin to appear, as well as painted ceramics with dancing creatures and later, geometric motifs. Cultures throughout the region began to make figurines, adornments and decorated jade implements by about 3500 BCE.

jade carvings begin to appear, as well as painted ceramics with dancing creatures and later, geometric motifs. Cultures throughout the region began to make figurines, adornments and decorated jade implements by about 3500 BCE.

The first Chinese dynasty ï¾– the Xia ï¾– was a Bronze Age people, and with the metals available to them, they made knives, awls, bells and jewelry. The Shang dynasty ruled from about the 17th century to about 1050 BCE, and the dynasty is noted for the extraordinary bronzework that emerged under their rule. Some of these pieces were cast using multiple ceramic molds, which is a technological advancement without parallel in ancient cultures. Gold and

The first Chinese dynasty ï¾– the Xia ï¾– was a Bronze Age people, and with the metals available to them, they made knives, awls, bells and jewelry. The Shang dynasty ruled from about the 17th century to about 1050 BCE, and the dynasty is noted for the extraordinary bronzework that emerged under their rule. Some of these pieces were cast using multiple ceramic molds, which is a technological advancement without parallel in ancient cultures. Gold and ![]() jade are found throughout East Asia during this period.

jade are found throughout East Asia during this period.

The brilliance of the Zhou dynasty followed, who ruled from the 11th to about the 3rd century BCE and under whom bronze objects were remarkably inlaid with precious metals. Headdresses fashioned during this period are often symmetrical and repetitive in their design: signs invested with sociological significance are alternated throughout such pieces. Some wall paintings show women wearing gems strung across their foreheads on gold diadems; these headpieces often taper at the sides from a central peak and show influence of cultural trade with Greece. Greek influence continued into the new millennium, especially visible through the widespread use of Greek motifs such as dolphins and amphorae.

The brilliance of the Zhou dynasty followed, who ruled from the 11th to about the 3rd century BCE and under whom bronze objects were remarkably inlaid with precious metals. Headdresses fashioned during this period are often symmetrical and repetitive in their design: signs invested with sociological significance are alternated throughout such pieces. Some wall paintings show women wearing gems strung across their foreheads on gold diadems; these headpieces often taper at the sides from a central peak and show influence of cultural trade with Greece. Greek influence continued into the new millennium, especially visible through the widespread use of Greek motifs such as dolphins and amphorae.

The Tao Te Ching was written during the late Zhou period, a founding text of Taoism stressing the union of man with the forces of nature. Nature has always played a large role in the art and craft of the Chinese. Animals were carved onto pendants that were made into earrings ï¾– one of the most popular types of jewelry in ancient China, worn by both men and women. Bracelets too were worn by both sexes, and often were decorated with animal figures. Phoenixes, lions and fu dogs were especially popular motifs.

The Tao Te Ching was written during the late Zhou period, a founding text of Taoism stressing the union of man with the forces of nature. Nature has always played a large role in the art and craft of the Chinese. Animals were carved onto pendants that were made into earrings ï¾– one of the most popular types of jewelry in ancient China, worn by both men and women. Bracelets too were worn by both sexes, and often were decorated with animal figures. Phoenixes, lions and fu dogs were especially popular motifs.

Necklaces were also frequently hung with animal heads cast from gold. Necklaces were sometimes pectorals ï¾– a form of pendant that runs throughout the ancient world from Egypt to East Asia. Torques were also an enduring style of neckpiece that are still made today by the Yao, a tribe that has migrated throughout China. Torques are usually silver, sometimes melted down from coins and fashioned into solid rings around the neck that are often engraved and include powerful figurative symbols such as dragons and fish. Silver, however, wasn't used with much regularity in China until the 7th century AD, so it is likely that early torques were fashioned from bronze and possibly gold.

Necklaces were also frequently hung with animal heads cast from gold. Necklaces were sometimes pectorals ï¾– a form of pendant that runs throughout the ancient world from Egypt to East Asia. Torques were also an enduring style of neckpiece that are still made today by the Yao, a tribe that has migrated throughout China. Torques are usually silver, sometimes melted down from coins and fashioned into solid rings around the neck that are often engraved and include powerful figurative symbols such as dragons and fish. Silver, however, wasn't used with much regularity in China until the 7th century AD, so it is likely that early torques were fashioned from bronze and possibly gold.

Images of pectorals and torques and the like are found in paintings or carved into reliefs and it's through such representations as well as through actual findings of ancient jewelry that we know they existed. Many of these representations suggest that jewelry was an indicator of social status and class. Armlets of the wealthy included horned griffins inlaid with glass and jewels; bracelets of this period were similarly encrusted with stones. As of the mid 8th century BCE, the Chinese were already using two or more machines at once to perform precision carving work on

Images of pectorals and torques and the like are found in paintings or carved into reliefs and it's through such representations as well as through actual findings of ancient jewelry that we know they existed. Many of these representations suggest that jewelry was an indicator of social status and class. Armlets of the wealthy included horned griffins inlaid with glass and jewels; bracelets of this period were similarly encrusted with stones. As of the mid 8th century BCE, the Chinese were already using two or more machines at once to perform precision carving work on ![]() jade. Rings have been found in the tombs of Chinese noblemen that clearly were carved by a machine that could move both around and forward at the same time, cutting grooves in a way that otherwise hasn't been discovered in any culture until Greece in the first century AD. Some rings were made to be seals, so that business transactions could be signed with the impression of their beautiful lacework inscriptions and animal ornamentation.

jade. Rings have been found in the tombs of Chinese noblemen that clearly were carved by a machine that could move both around and forward at the same time, cutting grooves in a way that otherwise hasn't been discovered in any culture until Greece in the first century AD. Some rings were made to be seals, so that business transactions could be signed with the impression of their beautiful lacework inscriptions and animal ornamentation.

The Qin dynasty ruled from 221 to 206 BCE ï¾– a short period of time during which the Chinese state was unified and the Great Wall of China was built, as well as other impressive construction efforts including the creation of a life-size terracotta army of more than 7000 figures intended to accompany the emperor into the afterlife in his tomb. Pendants designed to hang down onto the temple have been found in these tombs; they are rectangular and include compositions of simple narratives carved in metal. A civil war followed the Qin and out of chaos emerged the Western Han dynasty.

The Qin dynasty ruled from 221 to 206 BCE ï¾– a short period of time during which the Chinese state was unified and the Great Wall of China was built, as well as other impressive construction efforts including the creation of a life-size terracotta army of more than 7000 figures intended to accompany the emperor into the afterlife in his tomb. Pendants designed to hang down onto the temple have been found in these tombs; they are rectangular and include compositions of simple narratives carved in metal. A civil war followed the Qin and out of chaos emerged the Western Han dynasty.

The Hans ruled from 206 BCE to 220 CE, expanding the territory of the state to include Korea, Vietnam, Mongolia and Central Asia and establishing the Silk Road in Central Asia. This was a trade route with the Mediterranean world. Historically, the Chinese pacified Mongolian nomads by bribing them, and the nomads would trade these goods with people west of them. Cities began to develop along this route and all sorts of goods and religions were traded. Buddhism spread to China along this route from India, where Ashoka the Great had made it his mission to propagate the faith. Buddhist symbols were soon prevalent in Chinese jewelry. Later, under the Tang, when the Silk Road was at its peak in terms of traffic, Judaism, Islam and Christianity arrived in China as well.

The Hans ruled from 206 BCE to 220 CE, expanding the territory of the state to include Korea, Vietnam, Mongolia and Central Asia and establishing the Silk Road in Central Asia. This was a trade route with the Mediterranean world. Historically, the Chinese pacified Mongolian nomads by bribing them, and the nomads would trade these goods with people west of them. Cities began to develop along this route and all sorts of goods and religions were traded. Buddhism spread to China along this route from India, where Ashoka the Great had made it his mission to propagate the faith. Buddhist symbols were soon prevalent in Chinese jewelry. Later, under the Tang, when the Silk Road was at its peak in terms of traffic, Judaism, Islam and Christianity arrived in China as well.

The Tang and Song Dynasties saw Chinese culture at a very advanced status in terms of art, craft, and philosophy. Headdresses were constructed that looked something like the tents of desert nomads: gold wrapped around the head but extended up vertically and then was topped off with a separate, peaked metal structure. Both sections of such crowns were decorated with figures and ornaments, also made of precious metals and stones. Cloisonn� arrived in China during this period and although it was from Central Asia and originally reserved for the emperor and his court, it became a popular method of decoration still closely associated with China today and now widely available. The wealth of the country was pronounced during the Song dynasty because of great food surpluses and with excess came social elite that invigorated cultural production. Repouss� became a common technique in jewelry making.

The Tang and Song Dynasties saw Chinese culture at a very advanced status in terms of art, craft, and philosophy. Headdresses were constructed that looked something like the tents of desert nomads: gold wrapped around the head but extended up vertically and then was topped off with a separate, peaked metal structure. Both sections of such crowns were decorated with figures and ornaments, also made of precious metals and stones. Cloisonn� arrived in China during this period and although it was from Central Asia and originally reserved for the emperor and his court, it became a popular method of decoration still closely associated with China today and now widely available. The wealth of the country was pronounced during the Song dynasty because of great food surpluses and with excess came social elite that invigorated cultural production. Repouss� became a common technique in jewelry making.

By the end of the 15th century, the Silk Road had mostly stopped being a cultural trade route. China's trade policies under the Ming Dynasty (618-900 CE) had become largely isolationist, and sea routes had become a faster and less expensive way to transmit goods than passing them through infinite middlemen on the Silk Road. As the country became more and more isolated from the rest of the world, the differences between Chinese jewelry and that of other Central Asian or Middle Eastern countries became more pronounced. Motifs carved into jewelry became more specifically based in Chinese folklore, and forms too became more particular to the place. Jade was preferred over any other stone: valued for its qualities of hardness, durability and beauty, it was often compared with positive regard to human characteristics and took on a significance that prompted craftsmen to incorporate it into weaponry as well as jewelry. Blue had always been a color favored by craftsmen and the elite, and was incorporated into jewelry design via blue kingfisher feathers as well as blue gems.

By the end of the 15th century, the Silk Road had mostly stopped being a cultural trade route. China's trade policies under the Ming Dynasty (618-900 CE) had become largely isolationist, and sea routes had become a faster and less expensive way to transmit goods than passing them through infinite middlemen on the Silk Road. As the country became more and more isolated from the rest of the world, the differences between Chinese jewelry and that of other Central Asian or Middle Eastern countries became more pronounced. Motifs carved into jewelry became more specifically based in Chinese folklore, and forms too became more particular to the place. Jade was preferred over any other stone: valued for its qualities of hardness, durability and beauty, it was often compared with positive regard to human characteristics and took on a significance that prompted craftsmen to incorporate it into weaponry as well as jewelry. Blue had always been a color favored by craftsmen and the elite, and was incorporated into jewelry design via blue kingfisher feathers as well as blue gems.

The last Chinese Dynasty was the Qing, Manchus who took over from the Ming in 1644 and lasted until 1912. The Qing expanded the Chinese territory into Inner Mongolia, Manchuria, and Tibet, and the influence of these cultures is clear in terms of many of the designs and techniques used in jewelry making in China during the period. Pearls were exceedingly popular between the 17th and 19th centuries, especially those that came from Manchurian fresh water mussels. Strands of pearls would have hung down from the sides of elaborate headdresses of the period. The Qing stance towards Europe was defensive until the late 19th century, when China opened up its borders to foreign trade and missionary activity. This allowed for opium for British India to enter the country, and China engaged in war with Britain, which loosened the control the Emperor had over his country. War and opium led to economic decline, and cultural production accordingly was slowed.

The last Chinese Dynasty was the Qing, Manchus who took over from the Ming in 1644 and lasted until 1912. The Qing expanded the Chinese territory into Inner Mongolia, Manchuria, and Tibet, and the influence of these cultures is clear in terms of many of the designs and techniques used in jewelry making in China during the period. Pearls were exceedingly popular between the 17th and 19th centuries, especially those that came from Manchurian fresh water mussels. Strands of pearls would have hung down from the sides of elaborate headdresses of the period. The Qing stance towards Europe was defensive until the late 19th century, when China opened up its borders to foreign trade and missionary activity. This allowed for opium for British India to enter the country, and China engaged in war with Britain, which loosened the control the Emperor had over his country. War and opium led to economic decline, and cultural production accordingly was slowed.

This does not mean, of course, that nothing of note was produced in terms of ornamentation during this period. In fact, some of the most amazing Chinese antiques date from the Qing dynasty, including astonishingly long fingernail guards like elephant tusks for the nails, woven out of gold filigree or tortoise shell. Silver was a major part of Chinese jewelry during the 18th century. Jade ï¾– both green and white ï¾– was used to make simple spiral bangles. Some bracelets used both white and green

This does not mean, of course, that nothing of note was produced in terms of ornamentation during this period. In fact, some of the most amazing Chinese antiques date from the Qing dynasty, including astonishingly long fingernail guards like elephant tusks for the nails, woven out of gold filigree or tortoise shell. Silver was a major part of Chinese jewelry during the 18th century. Jade ï¾– both green and white ï¾– was used to make simple spiral bangles. Some bracelets used both white and green ![]() jade, allowing the natural imperfections of stones to become a part of the unique design of a piece of jewelry. Chinese craftsmen had a knack for knowing when to impose their own design on a stone and when to leave it au natural: upon finding a particularly interesting jadeite pebble, they might have set its irregular shape into an intricate, elegant ring, allowing the stone to be itself within their carefully constructed setting. Mangrove root was forced into circular shapes and lacquered to make beautiful bracelets trimmed with woven silver wire. Hairpins with narcissus flowers cast in gold and trimmed with blue kingfisher feathers and carved

jade, allowing the natural imperfections of stones to become a part of the unique design of a piece of jewelry. Chinese craftsmen had a knack for knowing when to impose their own design on a stone and when to leave it au natural: upon finding a particularly interesting jadeite pebble, they might have set its irregular shape into an intricate, elegant ring, allowing the stone to be itself within their carefully constructed setting. Mangrove root was forced into circular shapes and lacquered to make beautiful bracelets trimmed with woven silver wire. Hairpins with narcissus flowers cast in gold and trimmed with blue kingfisher feathers and carved ![]() amethyst graced the heads of noblewomen and gorgeous pendants were created to display special carvings of mythical beasts.

amethyst graced the heads of noblewomen and gorgeous pendants were created to display special carvings of mythical beasts.

The Republic of China was established in 1912, ending imperial rule in China. In the early twentieth century, natural patterns such as birds and flowers were carved into

The Republic of China was established in 1912, ending imperial rule in China. In the early twentieth century, natural patterns such as birds and flowers were carved into ![]() jade brooches, which were then set into gold borders and accented with floral projections of diamonds. Ivory too was fashioned into bangles, as well as burnt rock crystal and

jade brooches, which were then set into gold borders and accented with floral projections of diamonds. Ivory too was fashioned into bangles, as well as burnt rock crystal and ![]() amber beads. Chiang Kai-shek unified the country in the late 1920s, but was forced to retreat to Taiwan in 1949, when the Communist Party of China led by Mao Zedong established the People's Republic of China on the mainland. Taiwan was then called the Republic of China. Beginning in 1950, economic policy on the mainland left much of the educational, economic and cultural systems in states of distress. Jewelry was unpopular in China under the Communist rule. Beliefs in the supernatural power of stones ï¾– for luck, for instance ï¾– were banned as superstitious during the Cultural Revolution. Beauty was still always stressed as rewarding for women, and Communists did adorn themselves, but the acquisition of personal property was frowned upon under anti-capitalist legislation. Of course, again, this did not mean that jewelry was not produced or consumed by leaders, but the culture of production did become more elite and ornamentation outside of the top circles was very minimal and conservative, to say the least.

amber beads. Chiang Kai-shek unified the country in the late 1920s, but was forced to retreat to Taiwan in 1949, when the Communist Party of China led by Mao Zedong established the People's Republic of China on the mainland. Taiwan was then called the Republic of China. Beginning in 1950, economic policy on the mainland left much of the educational, economic and cultural systems in states of distress. Jewelry was unpopular in China under the Communist rule. Beliefs in the supernatural power of stones ï¾– for luck, for instance ï¾– were banned as superstitious during the Cultural Revolution. Beauty was still always stressed as rewarding for women, and Communists did adorn themselves, but the acquisition of personal property was frowned upon under anti-capitalist legislation. Of course, again, this did not mean that jewelry was not produced or consumed by leaders, but the culture of production did become more elite and ornamentation outside of the top circles was very minimal and conservative, to say the least.

In the 1990s, a second generation of Party leaders implemented political and economic reforms that launched China's economic development. The region is now one of the world's most robust economies and with the relaxation of stringent Communist rules, jewelry is popular in China. In the 1990s, women favored gold and diamonds because they were regarded as investments. Rubies have crept into contemporary Chinese style along with amethysts and emeralds.

In the 1990s, a second generation of Party leaders implemented political and economic reforms that launched China's economic development. The region is now one of the world's most robust economies and with the relaxation of stringent Communist rules, jewelry is popular in China. In the 1990s, women favored gold and diamonds because they were regarded as investments. Rubies have crept into contemporary Chinese style along with amethysts and emeralds.

Korea is situated south of Russia and China and west of Japan. Its history begins 4700 years ago with the Gojoseon people, descendents of Altaic tribes who settled in Manchuria, China and the Korean peninsula. This was a prospering Bronze Age civilization and Korean bronzework is said to have been quite distinctive from that in the surrounding region. Most metal was reserved for weaponry, but geometric patterns adorn less practical objects such as mirrors and some

Korea is situated south of Russia and China and west of Japan. Its history begins 4700 years ago with the Gojoseon people, descendents of Altaic tribes who settled in Manchuria, China and the Korean peninsula. This was a prospering Bronze Age civilization and Korean bronzework is said to have been quite distinctive from that in the surrounding region. Most metal was reserved for weaponry, but geometric patterns adorn less practical objects such as mirrors and some ![]() jade ornaments have been found in tombs dating from 900 BCE.

jade ornaments have been found in tombs dating from 900 BCE.

The region was ruled in the early Common Era by Three Kingdoms that competed with one another and at times with China. In 108 BC, the Chinese Han Dynasty began to make inroads in terms of establishing command posts in the peninsula; although all four posts had fallen by 313 AD, waves of immigration ensured that Chinese culture was a part of Korean society ï¾– for one thing, the Chinese brought silversmithing techniques to Korea. During this period, crowns, belts, hairpins, pendants and other forms of personal decoration were lavishly fashioned out of gold. Gold pendants were worn as earrings and hung from crowns and have been found in royal tombs. They were made of sheets of gold or beaded gold wire, sometimes in combination to form delicate designs. Jade was also popular in the Three Kingdoms period, and was used to make comma-shaped and tubular beads.

The region was ruled in the early Common Era by Three Kingdoms that competed with one another and at times with China. In 108 BC, the Chinese Han Dynasty began to make inroads in terms of establishing command posts in the peninsula; although all four posts had fallen by 313 AD, waves of immigration ensured that Chinese culture was a part of Korean society ï¾– for one thing, the Chinese brought silversmithing techniques to Korea. During this period, crowns, belts, hairpins, pendants and other forms of personal decoration were lavishly fashioned out of gold. Gold pendants were worn as earrings and hung from crowns and have been found in royal tombs. They were made of sheets of gold or beaded gold wire, sometimes in combination to form delicate designs. Jade was also popular in the Three Kingdoms period, and was used to make comma-shaped and tubular beads.

In 676 AD, the Silla Kingdom had unified the peninsula. China too was experiencing political unity under the Tang and a central government was functioning in Japan as well. This was a period of real stability throughout East Asia, and it was a time when the cultures willingly shared their jewelry and cultural products with one another, often as tribute from one court to another. During the 7th and 8th centuries, Arab traders frequently made their way into Korea via the Silk Road, and they made much mention of the prevalence of gold in the region. Common people were not allowed to wear this gold, however, nor were they allowed to wear silver or silk. Such finery was reserved for the elite.

In 676 AD, the Silla Kingdom had unified the peninsula. China too was experiencing political unity under the Tang and a central government was functioning in Japan as well. This was a period of real stability throughout East Asia, and it was a time when the cultures willingly shared their jewelry and cultural products with one another, often as tribute from one court to another. During the 7th and 8th centuries, Arab traders frequently made their way into Korea via the Silk Road, and they made much mention of the prevalence of gold in the region. Common people were not allowed to wear this gold, however, nor were they allowed to wear silver or silk. Such finery was reserved for the elite.

After several stages of further unrest, the Goryeo Dynasty was established in 936, from which dynasty the current name of Korea derives. A treaty signed with the Mongol Empire during this period enabled cultural cross-fertilization: Mongolian queens arrived in Korea to marry Goryeo kings and brought with them the fashion of their provinces. The aristocracy of this period had a taste for luxury unprecedented in the country's history, and the various celadon lacquered effects that have been found in archaeological sites are elegant, simple and laced with naturalistic symbolism such as dragon heads and vines.

After several stages of further unrest, the Goryeo Dynasty was established in 936, from which dynasty the current name of Korea derives. A treaty signed with the Mongol Empire during this period enabled cultural cross-fertilization: Mongolian queens arrived in Korea to marry Goryeo kings and brought with them the fashion of their provinces. The aristocracy of this period had a taste for luxury unprecedented in the country's history, and the various celadon lacquered effects that have been found in archaeological sites are elegant, simple and laced with naturalistic symbolism such as dragon heads and vines.

During the Goryeo Dynasty, artisans began engraving designs into

During the Goryeo Dynasty, artisans began engraving designs into ![]() jade objects, and during the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), jade actually began to be made into a diverse array of objects including hairpins and jewelry boxes. Really subtle shapes could be derived out of the stone, and because of the skill involved in such craft, only royalty and aristocrats were allowed to own jade objects. Strict neo-Confucianism had arisen during this period as well, and in fact much of the craft produced during the Joseon Dynasty had a practical function. Still, when one looks at jewelry from this period, one finds the Korean love of color at its height. For example, one hairpin from the 19th century is a slender dark silver rod culminating in a bit of silver leaf that flanks a twig of bright pink coral in its completely natural shape and form. Coral was worn by upper class women in the winter, perhaps to brighten up cold and snowy days. A set of three hairpins from the 18th century were even more remarkable, each similarly structured on a long silver pin but crowned with a cluster of cloisonn� butterflies and phoenixes on springs of silver thread flouncing like a multicolored dandelion. Moveable parts made these hairpins especially cute, and coral,

jade objects, and during the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), jade actually began to be made into a diverse array of objects including hairpins and jewelry boxes. Really subtle shapes could be derived out of the stone, and because of the skill involved in such craft, only royalty and aristocrats were allowed to own jade objects. Strict neo-Confucianism had arisen during this period as well, and in fact much of the craft produced during the Joseon Dynasty had a practical function. Still, when one looks at jewelry from this period, one finds the Korean love of color at its height. For example, one hairpin from the 19th century is a slender dark silver rod culminating in a bit of silver leaf that flanks a twig of bright pink coral in its completely natural shape and form. Coral was worn by upper class women in the winter, perhaps to brighten up cold and snowy days. A set of three hairpins from the 18th century were even more remarkable, each similarly structured on a long silver pin but crowned with a cluster of cloisonn� butterflies and phoenixes on springs of silver thread flouncing like a multicolored dandelion. Moveable parts made these hairpins especially cute, and coral, ![]() amber,

amber, ![]() agate, and red and green jade made for a very surprising bouquet.

agate, and red and green jade made for a very surprising bouquet.

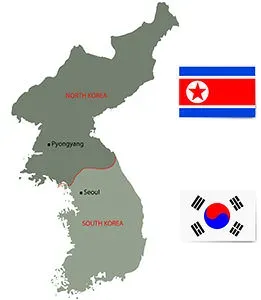

In the late 19th century, Korea was for a time annexed by Japan. Western influence became predominant, and some traditional forms were lost. After WWII and a short period in which the Soviet Union was supposed to administer Korea's northern region and the US was supposed to administer the south, the peninsula was divided into North and South Korea. During the Korean War, the United States bombed North Korea, destroying most North Korean cities. The peninsula remains divided ï¾– the south is a democratic state and the north is communist ï¾– but jewelry design in the region remains colorful.

In the late 19th century, Korea was for a time annexed by Japan. Western influence became predominant, and some traditional forms were lost. After WWII and a short period in which the Soviet Union was supposed to administer Korea's northern region and the US was supposed to administer the south, the peninsula was divided into North and South Korea. During the Korean War, the United States bombed North Korea, destroying most North Korean cities. The peninsula remains divided ï¾– the south is a democratic state and the north is communist ï¾– but jewelry design in the region remains colorful.

Japan is a group of islands located east of China, Korea and Russia whose history dates as far back as the Upper Paleolithic period. Personal adornment in Japan is an interesting story. Cultural production in Japan has been constant and incredible since it began, including pottery, literature, integration of philosophies from surrounding cultures, etc. Clothing, architecture and flower arranging are all evolving art forms that have been taken seriously throughout Japan's history. Jewelry, however, was not something in which citizens of Japan took much interest over time, at least not in Western terms.

Japan is a group of islands located east of China, Korea and Russia whose history dates as far back as the Upper Paleolithic period. Personal adornment in Japan is an interesting story. Cultural production in Japan has been constant and incredible since it began, including pottery, literature, integration of philosophies from surrounding cultures, etc. Clothing, architecture and flower arranging are all evolving art forms that have been taken seriously throughout Japan's history. Jewelry, however, was not something in which citizens of Japan took much interest over time, at least not in Western terms.

Comma shaped pendants not usually longer than an inch have been found in archaeological digs that date from about 1000 BCE to the 6th century AD, carved of green

Comma shaped pendants not usually longer than an inch have been found in archaeological digs that date from about 1000 BCE to the 6th century AD, carved of green ![]() jade and subsequently out of glass. Sometimes such beads appeared to have been strung in a necklace. Gold rings have been found that date from the 6th century AD, but this fashion only seems to have been popular for about 200 years. Despite contact with many cultures for which jewelry was popular ï¾– from China to Portugal in the 16th century ï¾– jewelry did not catch on as a fad among Japanese women. This is not to say that the country was not equipped to produce jewelry - crystal beads have been found from early periods, and the Japanese went through all the metalworking and ceramicist periods that surrounding cultures went through.

jade and subsequently out of glass. Sometimes such beads appeared to have been strung in a necklace. Gold rings have been found that date from the 6th century AD, but this fashion only seems to have been popular for about 200 years. Despite contact with many cultures for which jewelry was popular ï¾– from China to Portugal in the 16th century ï¾– jewelry did not catch on as a fad among Japanese women. This is not to say that the country was not equipped to produce jewelry - crystal beads have been found from early periods, and the Japanese went through all the metalworking and ceramicist periods that surrounding cultures went through.

Instead of rings and pendants, women readily wore hair combs and fans when attending events. Clothing was adorned with braided cords known as obi from which hung small sculptural boxes called inro which were necessary for carrying small objects, as kimonos do not have pockets. The fastener that kept the cord fastened to the obi was called a netsuke and these too were quite sculptural. Adorable little monkeys and laughing Buddhas were carved into toggles between one and three inches tall. At times netsuke were so intricately carved that light shone through their lacelike forms. They were carved from many materials, including especially ivory and hard woods, with metal, coral, lacquer and other materials used as accents. Sometimes netsuke had hidden surprises built into them, such as moving parts or additional compartments were items could be stored.

Instead of rings and pendants, women readily wore hair combs and fans when attending events. Clothing was adorned with braided cords known as obi from which hung small sculptural boxes called inro which were necessary for carrying small objects, as kimonos do not have pockets. The fastener that kept the cord fastened to the obi was called a netsuke and these too were quite sculptural. Adorable little monkeys and laughing Buddhas were carved into toggles between one and three inches tall. At times netsuke were so intricately carved that light shone through their lacelike forms. They were carved from many materials, including especially ivory and hard woods, with metal, coral, lacquer and other materials used as accents. Sometimes netsuke had hidden surprises built into them, such as moving parts or additional compartments were items could be stored.

Natural materials in general have long been used to fashion exceptional objects in Japanese culture, and when the Japanese encountered symmetrical, rational forms in Chinese craft, they incorporated them into their own aesthetic, often favoring the irregular natural forms at the core of ever material.

Natural materials in general have long been used to fashion exceptional objects in Japanese culture, and when the Japanese encountered symmetrical, rational forms in Chinese craft, they incorporated them into their own aesthetic, often favoring the irregular natural forms at the core of ever material.

In the mid 19th century, wealthy, fashionable Japanese women began wearing rings with their kimonos. Japanese royalty began wearing jewelry cast with the copper and silver alloy Shibuichi. Formerly used primarily for weaponry, Shibuichi began being used for decorative arts and jewelry after the Meiji period. This is true of other traditional metalworking crafts as well. Japan succeeded in rising to the status of a world power under the Emperor Meiji. This period ï¾– 1868 to 1912 ï¾– was a period of intense and deliberate internationalism, and while the government was engaged in this on many levels, the commercial level of cultural exchange is an important one, not to be overlooked.

In the mid 19th century, wealthy, fashionable Japanese women began wearing rings with their kimonos. Japanese royalty began wearing jewelry cast with the copper and silver alloy Shibuichi. Formerly used primarily for weaponry, Shibuichi began being used for decorative arts and jewelry after the Meiji period. This is true of other traditional metalworking crafts as well. Japan succeeded in rising to the status of a world power under the Emperor Meiji. This period ï¾– 1868 to 1912 ï¾– was a period of intense and deliberate internationalism, and while the government was engaged in this on many levels, the commercial level of cultural exchange is an important one, not to be overlooked.

Western and generally international styles came pouring into Japanese manufacturers, including especially

Western and generally international styles came pouring into Japanese manufacturers, including especially ![]() diamond pieces. Brooches are an example of a Western jewelry type that was acceptable for Japanese tastes: brooches did not alter the body in the same way that earrings did. One of the arguments given to persuade women to begin wearing jewelry was that it was wearable art and not simply an unnecessary accessory. Likewise, from a European perspective, the opening of trade relations with Japan was incredibly influential. Conventionally Japanese motifs of fans, flowers, cattail weeds, dragons and insects were all expressed in Victorian English jewelry often using Japanese techniques as well, such as enameling and Shakudo, Shibuichi and Satsuma (metal inlay).

diamond pieces. Brooches are an example of a Western jewelry type that was acceptable for Japanese tastes: brooches did not alter the body in the same way that earrings did. One of the arguments given to persuade women to begin wearing jewelry was that it was wearable art and not simply an unnecessary accessory. Likewise, from a European perspective, the opening of trade relations with Japan was incredibly influential. Conventionally Japanese motifs of fans, flowers, cattail weeds, dragons and insects were all expressed in Victorian English jewelry often using Japanese techniques as well, such as enameling and Shakudo, Shibuichi and Satsuma (metal inlay).

Also around this time, Japanese innovators began experimenting with freshwater mussels to produce beautiful pearls that were lustrous and had colors never before seen in saltwater pearls. Far less expensive than natural pearls, these cultured products were a worldwide success for Mikimoto.

Also around this time, Japanese innovators began experimenting with freshwater mussels to produce beautiful pearls that were lustrous and had colors never before seen in saltwater pearls. Far less expensive than natural pearls, these cultured products were a worldwide success for Mikimoto.

Japan is now the world's second largest economy by GDP after the United States. What is popular in Japan now is absolutely dynamic; Japan is a leader in design and tastemaking. More conservative reports say that white gold, white diamonds and pearls are all very popular among the Japanese, but Japanese culture has become increasingly diversified. Some of the most distinctive designers and indeed individual consumers come out of Japan these days, and colored gemstone jewelry is a big trend.

Japan is now the world's second largest economy by GDP after the United States. What is popular in Japan now is absolutely dynamic; Japan is a leader in design and tastemaking. More conservative reports say that white gold, white diamonds and pearls are all very popular among the Japanese, but Japanese culture has become increasingly diversified. Some of the most distinctive designers and indeed individual consumers come out of Japan these days, and colored gemstone jewelry is a big trend.