The earliest ornaments in the Mediterranean evidently appeared in the Paleolithic Age: seashells were pierced with suspension holes. Jewelry as we know it today: beads, pendants, earrings and bracelets, began to be produced in the Neolithic Age which lasted from 6800 to 3300 BCE. During this period, adornments were made mainly from stone, clay, bone and seashell. Metal ornaments were extremely rare at this time, but some have been found around Thessaly and Macedonia that are quite beautiful: dangling earrings made of cut leaves of gold and silver bracelets that wind up the wrist like slinkies.

The earliest ornaments in the Mediterranean evidently appeared in the Paleolithic Age: seashells were pierced with suspension holes. Jewelry as we know it today: beads, pendants, earrings and bracelets, began to be produced in the Neolithic Age which lasted from 6800 to 3300 BCE. During this period, adornments were made mainly from stone, clay, bone and seashell. Metal ornaments were extremely rare at this time, but some have been found around Thessaly and Macedonia that are quite beautiful: dangling earrings made of cut leaves of gold and silver bracelets that wind up the wrist like slinkies.

During the next thousand years or so, Minoan goldsmiths created intricate pieces involving filigree and granulation, often based on naturalistic representations of animals and insects, and by the middle of the Bronze Age, new types of ornamentation had begun to appear in Greece, as well as more sophisticated techniques. Semi-precious stones began to be incorporated into the designs. Complicated engravings of scenes from battles and hunting have been found on some pieces dating from the height of the Mycenaean world. Many such pieces were gold plates intended to be fastened to the dress of royalty.

During the next thousand years or so, Minoan goldsmiths created intricate pieces involving filigree and granulation, often based on naturalistic representations of animals and insects, and by the middle of the Bronze Age, new types of ornamentation had begun to appear in Greece, as well as more sophisticated techniques. Semi-precious stones began to be incorporated into the designs. Complicated engravings of scenes from battles and hunting have been found on some pieces dating from the height of the Mycenaean world. Many such pieces were gold plates intended to be fastened to the dress of royalty.

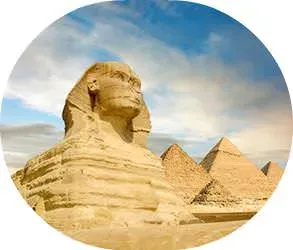

Much of what we know of ancient jewelry-making techniques and products derives from funerary situations: graves found in Greece and of course Egyptian pyramids. Egyptian funeral rites dictated that mummies were dressed and ornamented with a view to comfort in the afterlife. Owing to the elaborate care that the Egyptians bestowed on the preservation of their dead, we have a lot of information about their jewelry design. Egyptian wall paintings are also quite revealing about fashions of the times. Jewelry-making seems to have reached its peak in Egypt within the eighteenth and nineteenth dynasties of high Egyptian history and many of the most famous pieces date from that period: Queen Ahhotep's collection of ornaments dates from the 16th century B.C. and is among the richest and most various troves of intricate treasures in the world.

Much of what we know of ancient jewelry-making techniques and products derives from funerary situations: graves found in Greece and of course Egyptian pyramids. Egyptian funeral rites dictated that mummies were dressed and ornamented with a view to comfort in the afterlife. Owing to the elaborate care that the Egyptians bestowed on the preservation of their dead, we have a lot of information about their jewelry design. Egyptian wall paintings are also quite revealing about fashions of the times. Jewelry-making seems to have reached its peak in Egypt within the eighteenth and nineteenth dynasties of high Egyptian history and many of the most famous pieces date from that period: Queen Ahhotep's collection of ornaments dates from the 16th century B.C. and is among the richest and most various troves of intricate treasures in the world.

One major aspect of ancient Egyptian jewelry was that in addition to ornamentation, it generally served allegorical purposes as well. Among symbolic emblems, the scarab or beetle was very commonly represented in jewelry found in tombs. This insect was associated with life and rebirth, as was the god Khepera whose form was that of a gigantic scarab and whose duty it was to roll the sun like a huge ball through the sky, renewing its light to give life to the world. The ankh was another of the most powerful symbols in Pharaonic Egypt: a symbol of life often carried by gods and Pharaohs in surviving depictions from the time. Also quite popular was the symbolic eye of Horus the hawk-god, the cobra, which was an emblem of divine and royal sovereignty, the tet, an emblem of endurance and the human-headed hawk, an emblem of the soul. Another popular motif for pendants was the lotus flower.

One major aspect of ancient Egyptian jewelry was that in addition to ornamentation, it generally served allegorical purposes as well. Among symbolic emblems, the scarab or beetle was very commonly represented in jewelry found in tombs. This insect was associated with life and rebirth, as was the god Khepera whose form was that of a gigantic scarab and whose duty it was to roll the sun like a huge ball through the sky, renewing its light to give life to the world. The ankh was another of the most powerful symbols in Pharaonic Egypt: a symbol of life often carried by gods and Pharaohs in surviving depictions from the time. Also quite popular was the symbolic eye of Horus the hawk-god, the cobra, which was an emblem of divine and royal sovereignty, the tet, an emblem of endurance and the human-headed hawk, an emblem of the soul. Another popular motif for pendants was the lotus flower.

Egyptian jewelry was very colorful. Necklaces, scarabs, rings, and amulets were often inlaid with glazeware in blues, apple-greens, and later, yellow, violet, red, and white. Often the surfaces of jewelry were decorated with the application of colored stones into cells of gold prepared for them.

Egyptian jewelry was very colorful. Necklaces, scarabs, rings, and amulets were often inlaid with glazeware in blues, apple-greens, and later, yellow, violet, red, and white. Often the surfaces of jewelry were decorated with the application of colored stones into cells of gold prepared for them. ![]() Lapis lazuli,

Lapis lazuli, ![]() turquoise, root of

turquoise, root of ![]() emerald,

emerald, ![]() jasper, and obsidian were used most often, as well as various opaque glasses for imitative purposes. Egyptians used many processes of jewelry-making still currently available, and were highly skilled in soldering. Their designs sometimes included overlaying leaves of silver, bronze and stone in gold pieces.

jasper, and obsidian were used most often, as well as various opaque glasses for imitative purposes. Egyptians used many processes of jewelry-making still currently available, and were highly skilled in soldering. Their designs sometimes included overlaying leaves of silver, bronze and stone in gold pieces.

Following the sequence of ornaments from the head downwards, we begin with diadems or frontlets that Egyptians made to hang down over the temples. These were set with precious stones and set in a variety of ways or were sometimes inlaid with cloisonne representations of allegorical animals. Akhenaton, Pharaoh from 1350 - 1334 BCE, was the first to introduce the pierced ear in royal statuary, indicating the widespread use of earrings. Sovereign men may have worn earrings for sacred purposes but earrings were mostly popular among women, and then only late in Egyptian history. Those that do occur are simple, formed of a ring-shaped hook for piercing the lobe of the ear and hung with blossom-shaped or symbolic pendants. Sometimes large rings of various materials were fitted onto the upper part of the ear.

Following the sequence of ornaments from the head downwards, we begin with diadems or frontlets that Egyptians made to hang down over the temples. These were set with precious stones and set in a variety of ways or were sometimes inlaid with cloisonne representations of allegorical animals. Akhenaton, Pharaoh from 1350 - 1334 BCE, was the first to introduce the pierced ear in royal statuary, indicating the widespread use of earrings. Sovereign men may have worn earrings for sacred purposes but earrings were mostly popular among women, and then only late in Egyptian history. Those that do occur are simple, formed of a ring-shaped hook for piercing the lobe of the ear and hung with blossom-shaped or symbolic pendants. Sometimes large rings of various materials were fitted onto the upper part of the ear.

Frequently discovered in Egyptian tombs and wall paintings are necklaces. Many of them are chains consisting of various materials strung together with a large drop or figure in the center and smaller pendants strung at intervals beside it. Another variation on the necklace was the usekh collar, which covered the chest and shoulders and which was found on many mummies attached to the winding sheet. Such a collar is made of rows of cylinder-shaped beads with pendants gathered up at either end to the head of a lion, hawk, or lotus flower.

Frequently discovered in Egyptian tombs and wall paintings are necklaces. Many of them are chains consisting of various materials strung together with a large drop or figure in the center and smaller pendants strung at intervals beside it. Another variation on the necklace was the usekh collar, which covered the chest and shoulders and which was found on many mummies attached to the winding sheet. Such a collar is made of rows of cylinder-shaped beads with pendants gathered up at either end to the head of a lion, hawk, or lotus flower.

Egyptians also wore pectorals, worn on the breast, suspended by ribbons or chains and inlaid with jewels. They were made of metal, usually gilded bronze, and sometimes of glazed alabaster, steatite basalt or earthenware. Pectorals often included pictures of silhouetted relief, some of which were actually hieroglyphs and told stories. The pictures were designed according to mathematical formulas expressed through geometric symbolism. Important elements of the design were significantly situated within the design so as to lend meaning to the reading of the arrangement and to empower the usually royal wearer of the pectoral.

Egyptians also wore pectorals, worn on the breast, suspended by ribbons or chains and inlaid with jewels. They were made of metal, usually gilded bronze, and sometimes of glazed alabaster, steatite basalt or earthenware. Pectorals often included pictures of silhouetted relief, some of which were actually hieroglyphs and told stories. The pictures were designed according to mathematical formulas expressed through geometric symbolism. Important elements of the design were significantly situated within the design so as to lend meaning to the reading of the arrangement and to empower the usually royal wearer of the pectoral.

Bracelets, arm pieces, and rings are also very commonly found. Rings also served as a signet with the owner's emblem engraved on their surface. Some such rings are very cleverly designed so that ornamental scarabs and the like were exhibited until it was time to use the seal, at which point the scarab would revolve on wires, exhibiting the engraved side.

Bracelets, arm pieces, and rings are also very commonly found. Rings also served as a signet with the owner's emblem engraved on their surface. Some such rings are very cleverly designed so that ornamental scarabs and the like were exhibited until it was time to use the seal, at which point the scarab would revolve on wires, exhibiting the engraved side.

Egypt was in control of much of the Mediterranean until 1200 BCE, when Phoenicia came into its own as a dominant seapower, trading throughout the Mediterranean. Egyptian jewelry trends were picked up by the traveling Phoenicians who imported jewels and other articles of trade through Italy and Greece, spreading the ironworking of Etruscans and the symbology of Greece. Greece had been rather isolated from 1100 to 800 BCE, producing jewelry that was far simpler than it had been before: circles and bands had taken the place of elaborate Mycenaean pieces. With renewed "international" contact via the Phoenicians, their jewelry-making flowered again.

Egypt was in control of much of the Mediterranean until 1200 BCE, when Phoenicia came into its own as a dominant seapower, trading throughout the Mediterranean. Egyptian jewelry trends were picked up by the traveling Phoenicians who imported jewels and other articles of trade through Italy and Greece, spreading the ironworking of Etruscans and the symbology of Greece. Greece had been rather isolated from 1100 to 800 BCE, producing jewelry that was far simpler than it had been before: circles and bands had taken the place of elaborate Mycenaean pieces. With renewed "international" contact via the Phoenicians, their jewelry-making flowered again.

The Archaic period in Greece (600-475 BCE) saw very little goldwork perhaps because Persians controlled the Middle East and made very little gold available. By the 5th century, or what is known as the Classical period, Greeks used gold in the processes of repousse, chasing, engraving, intaglio, and soldering. Enameling reappeared, though it hadn't been used since the Mycenaean period. Diadems also reappeared as a form of ornamentation, and were often created with minute detailing. Earrings, pins, and bracelets were all popular. Sometimes girdles were decorated with gold, to accompany silken tassels that held garments to the waist, and in this case, the gold was fashioned to resemble a textile.

The Archaic period in Greece (600-475 BCE) saw very little goldwork perhaps because Persians controlled the Middle East and made very little gold available. By the 5th century, or what is known as the Classical period, Greeks used gold in the processes of repousse, chasing, engraving, intaglio, and soldering. Enameling reappeared, though it hadn't been used since the Mycenaean period. Diadems also reappeared as a form of ornamentation, and were often created with minute detailing. Earrings, pins, and bracelets were all popular. Sometimes girdles were decorated with gold, to accompany silken tassels that held garments to the waist, and in this case, the gold was fashioned to resemble a textile.

Gold became increasingly abundant as Greece began to have more and more contact with the East and with Egypt: Alexander the Great's conquests ushered in the Hellenistic age (330 - 27 BCE), during which period many and various colors of semi-precious stones were used to decorate bracelets, earrings, and other forms. Crescents were very popular shapes, even into the years of the Roman occupation after 27 BCE. Many different colors of stones were used during this period and enameling became less popular.

Gold became increasingly abundant as Greece began to have more and more contact with the East and with Egypt: Alexander the Great's conquests ushered in the Hellenistic age (330 - 27 BCE), during which period many and various colors of semi-precious stones were used to decorate bracelets, earrings, and other forms. Crescents were very popular shapes, even into the years of the Roman occupation after 27 BCE. Many different colors of stones were used during this period and enameling became less popular.

The Roman Empire (27 to 476 BCE) corresponds to a period of time in jewelry-making in the Western world during which the traces of many cultures can be found. Because the Romans had subdued the Etruscans, the Italians, and the Greeks, the handiwork of all these artisans were combined to create the extravagance for which the Empire is infamous. Romans were more passionate about precious stones and pearls and more lavish with their rings than any culture before them.

The Roman Empire (27 to 476 BCE) corresponds to a period of time in jewelry-making in the Western world during which the traces of many cultures can be found. Because the Romans had subdued the Etruscans, the Italians, and the Greeks, the handiwork of all these artisans were combined to create the extravagance for which the Empire is infamous. Romans were more passionate about precious stones and pearls and more lavish with their rings than any culture before them.