The continent of Africa is extremely diverse, and as we look at its history of jewelry making, it can be helpful to consider the land in terms of three regions: the Saharan region of the north, the Equatorial region, and the Savannah region that separates the two. These regions are especially different from one another because of their differences in climate, and climate has everything to do with the materials used to make jewelry.

The continent of Africa is extremely diverse, and as we look at its history of jewelry making, it can be helpful to consider the land in terms of three regions: the Saharan region of the north, the Equatorial region, and the Savannah region that separates the two. These regions are especially different from one another because of their differences in climate, and climate has everything to do with the materials used to make jewelry.

North Africa is covered by the Sahara, the largest desert in the world. These infertile gravel plains are home to the nomadic Berbers, Tuaregs and Moors, who weather freezing temperatures at night and sizzling temperatures during the day. Because the desert is so dry, there are very few materials available to make jewelry, but adornment is still a big part of society, and these people use materials from animal skins and from trade to fashion fascinating pieces.

North Africa is covered by the Sahara, the largest desert in the world. These infertile gravel plains are home to the nomadic Berbers, Tuaregs and Moors, who weather freezing temperatures at night and sizzling temperatures during the day. Because the desert is so dry, there are very few materials available to make jewelry, but adornment is still a big part of society, and these people use materials from animal skins and from trade to fashion fascinating pieces.

The Berbers are believed to have been the original inhabitants of North Africa. Invasions by the Carthaginians, Greeks, Romans, Goths, and finally Arabs in 684 AD affected the culture of the Berbers but through it all they retained their own language and ethnic traditions. Berbers inhabit the Atlas mountain ranges and the oases of the northern desert cities. They wear draped clothing, held with metal brooches and fabric belts.

The Berbers are believed to have been the original inhabitants of North Africa. Invasions by the Carthaginians, Greeks, Romans, Goths, and finally Arabs in 684 AD affected the culture of the Berbers but through it all they retained their own language and ethnic traditions. Berbers inhabit the Atlas mountain ranges and the oases of the northern desert cities. They wear draped clothing, held with metal brooches and fabric belts.

Jewelry, among Berbers, is a way of saving money, and usually the power in this respect is given to women: if she has been gifted a piece of jewelry, it is hers absolutely, and she may sell an ornament to buy something else or to provide for her family, even to buy land. Jewelry is like an investment in this culture, and the women are something like bankers, building up their collection of jewelry from childhood. Berber women prefer jewelry that is made for them personally. Many pieces are melted down and remade into new jewelry. It is rare to find antique pieces.

Jewelry, among Berbers, is a way of saving money, and usually the power in this respect is given to women: if she has been gifted a piece of jewelry, it is hers absolutely, and she may sell an ornament to buy something else or to provide for her family, even to buy land. Jewelry is like an investment in this culture, and the women are something like bankers, building up their collection of jewelry from childhood. Berber women prefer jewelry that is made for them personally. Many pieces are melted down and remade into new jewelry. It is rare to find antique pieces.

Gold is considered bad luck in Tuareg and Berber culture. In fact, the Prophet Mohammed disapproved of gold jewelry for men, but wore silver jewelry himself, and so by his example, men began to wear silver. Despite the fact that women are allowed to wear gold, silver is the most common metal used in this region.

Gold is considered bad luck in Tuareg and Berber culture. In fact, the Prophet Mohammed disapproved of gold jewelry for men, but wore silver jewelry himself, and so by his example, men began to wear silver. Despite the fact that women are allowed to wear gold, silver is the most common metal used in this region.

Berber pieces may be made with niello-work, enamel, engraving, repousse, and semi-precious stones. Some of their techniques , including cloisonne and filigree, are derivative of European cultures with whom the Berbers came in contact in the Medieval era, and pieces rendered through these methods still summon up images of that period.

Berber pieces may be made with niello-work, enamel, engraving, repousse, and semi-precious stones. Some of their techniques , including cloisonne and filigree, are derivative of European cultures with whom the Berbers came in contact in the Medieval era, and pieces rendered through these methods still summon up images of that period.

Berbers wear head ornaments, earrings, pendants, necklaces, rings, brooches, bracelets, and anklets. The earrings are enormous, and women generally wear many of the pieces that they own at all times. A Berber woman might wear a necklace composed of a central amulet, flanked by silver balls with cloisonne enamel, separated by clusters of coral, pate de verre, shells, and silver coins. Certain stones are chosen for medicinal properties at times as well; for example, carnelian is considered by Tuaregs to heal wounds and relieve cramps.

Berbers wear head ornaments, earrings, pendants, necklaces, rings, brooches, bracelets, and anklets. The earrings are enormous, and women generally wear many of the pieces that they own at all times. A Berber woman might wear a necklace composed of a central amulet, flanked by silver balls with cloisonne enamel, separated by clusters of coral, pate de verre, shells, and silver coins. Certain stones are chosen for medicinal properties at times as well; for example, carnelian is considered by Tuaregs to heal wounds and relieve cramps.

Men wear very little jewelry except for a variety of rings and watches, but they get their share of silver in the ornamentation of their personal effects. Silver-sheathed dagger cases can be evidence of the tribe and social rank of the man sporting the weapon, as can the case that holds a man's Koran.

Men wear very little jewelry except for a variety of rings and watches, but they get their share of silver in the ornamentation of their personal effects. Silver-sheathed dagger cases can be evidence of the tribe and social rank of the man sporting the weapon, as can the case that holds a man's Koran.

Tuareg jewelry tends towards the bold and geometric. It is often large and symmetrical in its design. The Tuareg Cross is passed down from father to son when the child hits puberty. Made of silver, its four points represent the four corners of the world. Muslim Tuaregs believe that the arms of the cross will disperse evil from the individual who wears it. The strong geometric shape of these crosses is accented always by interesting work on the body of the cross, small carvings and settings boldly decorate the pendants, which are used in modern times also as earrings for women. These designs are traditional, but are still traded on the contemporary market. Silver beads and pendants are traditionally made by melting down coins, but some commercial jewelry workshops produce copies of tribal jewelry using sheet metal.

Tuareg jewelry tends towards the bold and geometric. It is often large and symmetrical in its design. The Tuareg Cross is passed down from father to son when the child hits puberty. Made of silver, its four points represent the four corners of the world. Muslim Tuaregs believe that the arms of the cross will disperse evil from the individual who wears it. The strong geometric shape of these crosses is accented always by interesting work on the body of the cross, small carvings and settings boldly decorate the pendants, which are used in modern times also as earrings for women. These designs are traditional, but are still traded on the contemporary market. Silver beads and pendants are traditionally made by melting down coins, but some commercial jewelry workshops produce copies of tribal jewelry using sheet metal.

The Tuaregs did not, as a general rule, intermarry with the people from the Savannah, or with the Arabs, but the Moors did, and various evolutions in Moorish design can be traced to these points of contact. Arabs do wear gold, and so the jewelry of Moors includes filigreed gold pieces set with pearls, emeralds, or semi-precious stones. Diadems are worn at marriage ceremonies, and earrings, like those worn by Berber women, are huge. Bracelets and brooches were traditionally worn in pairs, and only recently are starting to be worn singly. Women's hair is sometimes wrapped in brass, as are ankles. Many beaded pieces are strung in wonderful patterns.

The Tuaregs did not, as a general rule, intermarry with the people from the Savannah, or with the Arabs, but the Moors did, and various evolutions in Moorish design can be traced to these points of contact. Arabs do wear gold, and so the jewelry of Moors includes filigreed gold pieces set with pearls, emeralds, or semi-precious stones. Diadems are worn at marriage ceremonies, and earrings, like those worn by Berber women, are huge. Bracelets and brooches were traditionally worn in pairs, and only recently are starting to be worn singly. Women's hair is sometimes wrapped in brass, as are ankles. Many beaded pieces are strung in wonderful patterns.

Throughout the Sahara, jewelry design has kept fairly close to tradition, but subtleties have changed. Large, heavy pieces with intricate detail are generally older, while new pieces are set with more speed and less expensive, flashier stones.

Throughout the Sahara, jewelry design has kept fairly close to tradition, but subtleties have changed. Large, heavy pieces with intricate detail are generally older, while new pieces are set with more speed and less expensive, flashier stones.

Some of the characteristics of Moorish jewelry are found in Morocco and Egypt; the northern countries of Africa are interconnected stylistically with Arabic tendencies from the Middle East as much as with tendencies from further south on the continent.

Some of the characteristics of Moorish jewelry are found in Morocco and Egypt; the northern countries of Africa are interconnected stylistically with Arabic tendencies from the Middle East as much as with tendencies from further south on the continent.

The Savannah stretches east from Senegal to Chad and separates the Sahara from the Equatorial forest. In the Savannah, gold is used profusely. The Fulani women of Mali wear gold earrings and the size of these pieces increases in proportion to the family's wealth. Brass and copper are also common because they are traded between North and West Africa along routes that cut through the dry land of the Savannah.

The Savannah stretches east from Senegal to Chad and separates the Sahara from the Equatorial forest. In the Savannah, gold is used profusely. The Fulani women of Mali wear gold earrings and the size of these pieces increases in proportion to the family's wealth. Brass and copper are also common because they are traded between North and West Africa along routes that cut through the dry land of the Savannah.

These metals are worn by men in the form of heavy head plaques and by women in the form of anklets, necklaces, bracelets and all sorts of other adornments. Of these ornaments, anklets are at times seen as the most significant: a girl wears them until she is ready to have children. Metalwork has been practiced since antiquity among these cultures, and the design of these pieces emulates other materials available in the region: brass ankle bracelets in Burkina Faso are in the form of rigid ropes.

These metals are worn by men in the form of heavy head plaques and by women in the form of anklets, necklaces, bracelets and all sorts of other adornments. Of these ornaments, anklets are at times seen as the most significant: a girl wears them until she is ready to have children. Metalwork has been practiced since antiquity among these cultures, and the design of these pieces emulates other materials available in the region: brass ankle bracelets in Burkina Faso are in the form of rigid ropes.

Besides formal rhymes between metals and other materials, jewelry in the Savannah sometimes takes on figurative form, and the form of animals that are relevant to the local habitat. In the Ivory Coast, Senufo bracelets are made of wrought iron and include renderings of sacred pythons cast by the lost-wax process. Rings in the form of African buffalo serve ritual purposes. Human faces are abstracted and worn as pendants of gold suspended from headdresses. Among the Dan tribe, ankle bracelets of stacks of bells are cast in brass. In Ghana, Ashanti founders make gold necklaces that they have made forever, but like the trend in the Sahara, their work has become larger and somewhat less refined as fine metals become more scarce.

Besides formal rhymes between metals and other materials, jewelry in the Savannah sometimes takes on figurative form, and the form of animals that are relevant to the local habitat. In the Ivory Coast, Senufo bracelets are made of wrought iron and include renderings of sacred pythons cast by the lost-wax process. Rings in the form of African buffalo serve ritual purposes. Human faces are abstracted and worn as pendants of gold suspended from headdresses. Among the Dan tribe, ankle bracelets of stacks of bells are cast in brass. In Ghana, Ashanti founders make gold necklaces that they have made forever, but like the trend in the Sahara, their work has become larger and somewhat less refined as fine metals become more scarce.

Ornamentation in the Savannah takes forms other than jewelry, including hair sculpture for women and ceremonial helmets for men. The women grease their hair with butter and decorate it with glass beads and metals. The helmets of men are fashioned from stiffened hides and decorated with gold leaf and wood ornaments. These are worn at ceremonies at the Ashanti courts. Men also wear massive gold rings, especially princes and dignitaries, and these are often created through the lost-wax process, a technique of bronze casting initiated in the thirteenth century.

Ornamentation in the Savannah takes forms other than jewelry, including hair sculpture for women and ceremonial helmets for men. The women grease their hair with butter and decorate it with glass beads and metals. The helmets of men are fashioned from stiffened hides and decorated with gold leaf and wood ornaments. These are worn at ceremonies at the Ashanti courts. Men also wear massive gold rings, especially princes and dignitaries, and these are often created through the lost-wax process, a technique of bronze casting initiated in the thirteenth century.

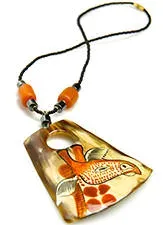

The Equatorial region encompasses much of Africa's forest and swamp forest terrain, although countries in this region also of course include savannah and coastline. Ivory is widely available through hunting in the equatorial region, and has long been a sacred material for use at first only by kings and now by important people who can afford it or whose position in society merits the bone. In Zaire, one finds ivory carved into figurative shapes, some of which represent ancestors and are worn for protection or as badges to mark initiation into society. In the Southwestern Congo, the Pende make masks of ivory to indicate that the wearer has undergone circumcision and initiation. In Cameroon, one finds colored ivory, dyed with plants, fruits and berries.

The Equatorial region encompasses much of Africa's forest and swamp forest terrain, although countries in this region also of course include savannah and coastline. Ivory is widely available through hunting in the equatorial region, and has long been a sacred material for use at first only by kings and now by important people who can afford it or whose position in society merits the bone. In Zaire, one finds ivory carved into figurative shapes, some of which represent ancestors and are worn for protection or as badges to mark initiation into society. In the Southwestern Congo, the Pende make masks of ivory to indicate that the wearer has undergone circumcision and initiation. In Cameroon, one finds colored ivory, dyed with plants, fruits and berries.

Trade is a major part of the economy of the Equatorial rain forest. Gold and ivory have been traded for glass beads, copper, brass and coral since the fifteenth century. The lost-wax process prevalent in the Savannah originated with the Yoruba in Nigeria, and it is still used by the Yoruba to create intricate brass ornamentation. Women wear collars fashioned through this process, royalty in Benin wear hip ornaments made this way, and wide bracelets worn to entice men are plaited out of brass and worn by women in Nigeria.

Trade is a major part of the economy of the Equatorial rain forest. Gold and ivory have been traded for glass beads, copper, brass and coral since the fifteenth century. The lost-wax process prevalent in the Savannah originated with the Yoruba in Nigeria, and it is still used by the Yoruba to create intricate brass ornamentation. Women wear collars fashioned through this process, royalty in Benin wear hip ornaments made this way, and wide bracelets worn to entice men are plaited out of brass and worn by women in Nigeria.

The Oba Benin ruler of the Yoruba wears a beaded crown fixed with birds and beaded veils to protect the public from the power of his gaze. He also holds a beaded staff. The Ogboni cult of Mother Earth observed by Southern Yoruba gave rise to many ritual articles. These are often made of ancient glass beads, or beads made from clay that supposedly was derived from discarded beads of long-ago kings.

The Oba Benin ruler of the Yoruba wears a beaded crown fixed with birds and beaded veils to protect the public from the power of his gaze. He also holds a beaded staff. The Ogboni cult of Mother Earth observed by Southern Yoruba gave rise to many ritual articles. These are often made of ancient glass beads, or beads made from clay that supposedly was derived from discarded beads of long-ago kings.

What is so fascinating about the jewelry of Africa is that despite centuries of interaction between tribes and other countries, the groups of craftsmen in each area have retained their respective investments in their own craft. Each area is tightly tied to its available materials and each type of jewelry is bound to mystical or social significance; borrowing symbols or materials from other cultures is meaningless and superfluous. Though techniques have changed somewhat, much of the decorative arts produced in Africa today are true to traditional stylistic roots.

What is so fascinating about the jewelry of Africa is that despite centuries of interaction between tribes and other countries, the groups of craftsmen in each area have retained their respective investments in their own craft. Each area is tightly tied to its available materials and each type of jewelry is bound to mystical or social significance; borrowing symbols or materials from other cultures is meaningless and superfluous. Though techniques have changed somewhat, much of the decorative arts produced in Africa today are true to traditional stylistic roots.